An industrial revolution based on inhumanity

I hope we don’t ignore the less attractive parts of our history one of which I want to describe this week. There is surely no more disgraceful story than the treatment meted out to those employed in the coal industry and sadly the employers in our area were among the worst offenders.

Things were bad in the Victorian era but as nothing compared with the scandalous situation in earlier centuries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrom 1606 Scottish colliers were enslaved as bonded labour, tied to their pit and employer to be bought or sold like so many wooden props or lengths of rail. Those who tried to leave could be brought back and punished by imprisonment or worse. Not until 1799 were they freed by law from this serfdom and only because the employers needed to recruit more men to work in the rapidly expanding industry.

But this ‘freedom’ did not stop the exploitation of women and young children. All over the district boys and girls, some as young as six years of age, found themselves in dark and dangerous places, hundreds of feet below the ground.

The full extent of this ill treatment was not revealed until 1842 when the remarkable testimonies of the children themselves were reported to Parliamentary Commissioners. From Redding to Bo’ness, Bantaskine to Kinnaird came horror stories that shamed all involved including two leading colliery owners, Carron Company and the Duke of Hamilton.

In Falkirk Rebbecca Simpson, aged 11, worked underground along with her sister pulling hutches of coal weighing seven hundred weight up a 200 yard slope fourteen times a day: “if it is difficult to draw, brother George [who was 14] helps us up the brae”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot far away in Redding, Thomas Walker, a 13 year-old coal hewer, usually worked a 13-hour shift beginning at about 2am.

In the same place a seven year-old trapper boy, David Guy, sat for hours operating a ventilation door by hand: “Its no very hard work, but unco lang, and I canna hardly get up the stair-pit when work is done”.

One of his fellow workers at Redding, nine year-old James Watson found the pit “gai dark … an awfu frightsome place”, and one of the inspectors visiting Stoney Rigg colliery met 17 year-old Margaret Hipps and was appalled by what he found: “She draws a bogie weighing 250 to 350 pounds along a passage 26-28 inches high ... it is almost incredible to believe that human beings can submit to such employment, crawling on hands and knees, harnessed like horses, and over soft slushy floors.”

Sadly, concern for the well-being of the workers was almost non-existent. Mary Sneddon from Bo’ness reported: “Brother Robert was killed on 21st January last: a piece of roof fell on his head and he died instantly. He was brought home, coffined and buried in Bo’ness kirk-yard. No one came to enquire how he was killed; they never do in this place.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

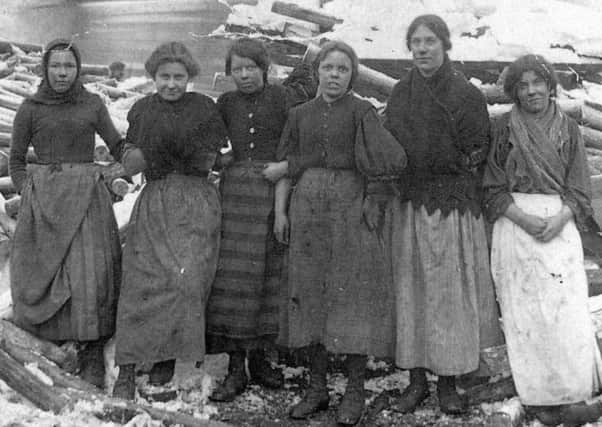

Hide AdThe outcry that followed the publication of the report led to a new law banning all females as well as boys under 10 from underground work and while this did not end the exploitation or improve working conditions it at least removed some of the worst excesses.

However it is a sobering thought that the industrial revolution which laid the foundation for much of our wealth and prosperity was based on such inhumanity.