Highs and lows of life for Victorian women

John Wilson’s father owned successful coal pits in Banton and in 1828 decided to extend his empire. He was attracted to South Bantaskine not only by the rich coal seams but because his family had taken part on the Jacobite side in the 1746 battle fought over the same land. The ironworks at Carron was hungry for vast quantities of coal and there were opportunities to earn a quick fortune.

John took over from his father in 1836 and set about developing the business and estate. In 1848 he further enhanced his influence by marrying Mary, daughter of the mighty James Russel of Arnotdale, Falkirk’s leading lawyer and man of business. It was a long and happy marriage of which John Wilson said “Prudence prevents me expressing more than the fact, in reference to my bosom friend, that God by these espousals hath blessed us with a happy home”. It was certainly a busy place because within a relatively short period the couple produced their large family and the original house was too small to hold them. The result was South Bantaskine House, completed around 1860. Ever conscious of the Jacobite connections John Wilson commissioned the famous stained glass windows now in the Howgate centre.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

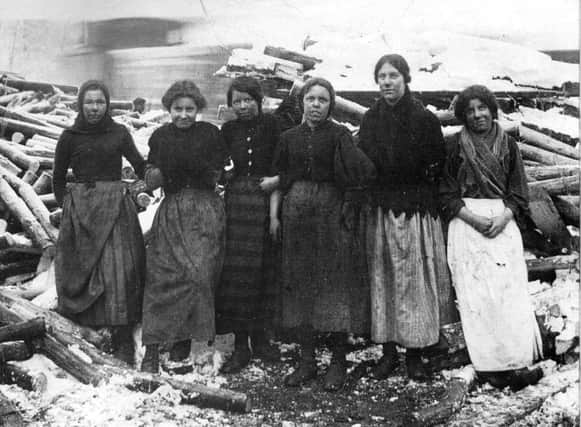

Hide AdFour miles away, Redding Colliery like all others in Scotland, no longer employed girls below ground following the exposure in 1844 of the suffering and exploitation which had been common for centuries. However that did not end the way in which women of all ages were put to work on the surface doing back-breaking, dirty and dangerous labour for paltry wages. By the time this picture was taken the Duke of Hamilton’s colliery at Redding was the biggest in Falkirk district with 370 men underground and 90 on the surface, many of them young women. No pretty frocks for them and precious little time or energy to enjoy the pleasures of life that filled the hours of their more fortunate ‘‘sisters’’ in South Bantaskine.

Like most men in his social position, John Wilson was an active churchman involved with the West Church on the Tanner’s Brae. By all accounts he was more concerned for the welfare of his colliers than many coal owners of the period though that wouldn’t have been too hard. Helping to alleviate the most obvious signs of suffering was one thing but changing the situation that brought it about was another. As the popular Victorian hymn reminded the faithful: ‘‘The rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate, He made the high and lowly, and ordered their estate’’.

But time brings change and three of the South Bantaskine sisters lived into old age in the new 20th century and were witness to the emancipation of women a century ago this year. It did not correct the wrongs of the past but it was a start at least.