Historian Ian Scott looks back at Falkirk’s canal network

and live on Freeview channel 276

Sometimes the changes bring new opportunities but frequently signal the start of darker days with uncertainty and insecurity for many.

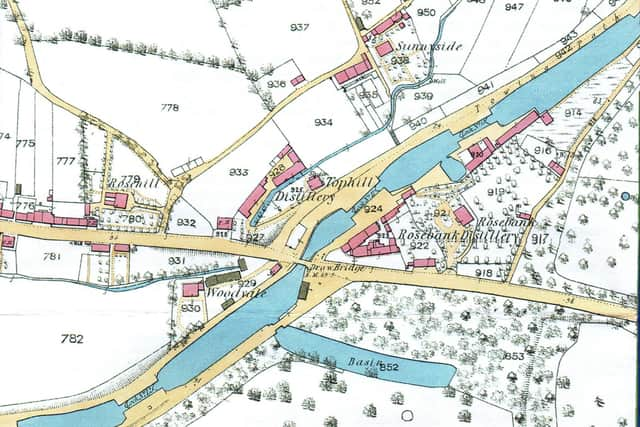

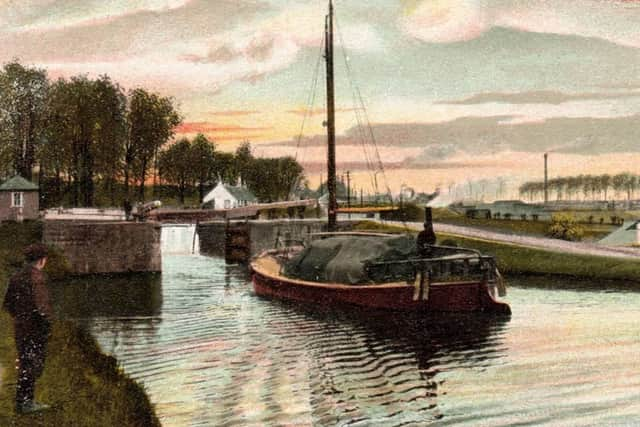

One such revolution occurred 250 years ago this year when engineers flooded the eastern end of the Great Canal destined to join the Forth to the Clyde. Now the promised advantages of the waterway would begin to make themselves felt and, within a few years, Falkirk was a completely different place, a relatively quiet rural village turned into a potential powerhouse of new industry. Walk the towpath of the canal from Grangemouth (which didn’t exist before then) to Bonnybridge and you will be following in the hoofprints of the great horses that once pulled laden barges of coal, grain, timber, iron ore and passengers by the thousand from one side of the country to the other.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe engineer responsible for this master work was John Smeaton who planned a 35-mile waterway over 50 feet wide and seven feet deep from the point where the Carron joined the Forth, to the Clyde near Bowling. A series of 20 locks would carry the barges north and west of Falkirk from Middlefield to Bainsford and on through Camelon and Bonnybridge to the summit at Wynford Lock, over 150 feet above sea level.

In 1767 a public company was formed with 1500 £100 shares subscribed to by the most powerful figures in the land. There were six dukes and 17 earls as well as the Lord Provosts of both Edinburgh and Glasgow but the biggest shareholder was Sir Lawrence Dundas of West Kerse. The canal would begin its journey on his land and, as a result, he stood to gain in every way from its success. Parliament approved the proposal in 1768 and in the same year the work began. It was a colossal undertaking, the greatest civil engineering project in Scotland since the Romans completed the Antonine Wall 1600 years before.

Smeaton’s salary as chief engineer was £500 and Robert McKell, his assistant, was paid £375. These were princely sums at the time when one of workmen was paid less than a shilling a day. McKell certainly earned his pay for he was in charge of the day-to-day work – searching out and buying timber, stone and clay, and engaging skilled masons as well as scores of labourers, the navigators or ‘navvies’, armed with pick and shovel who, by all accounts, fought, drank and dug themselves from Grangemouth all the way to the Clyde.

One can hardly imagine the impact on small communities of the arrival of these huge armies, living in temporary accommodation and disturbing the peace of the inhabitants. Their presence was resented by the local carters who thought their jobs would disappear and the records report regular vandalism, locks destroyed, equipment stolen and workers attacked. Even worse was the breaking down of the lock gate at Lock 16 allowing four miles of water to pour down through the workings towards the Glasgow Road at Rosebank. But their fears proved unfounded.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAll along the banks, workshops, warehouses, timber yards, sawmills, tile works, distilleries, chemical factories and coal stores appeared and with them new opportunities and many new people.

The Great Canal brought such change to our area that, even today, it influences our thinking long after the last barge was laid up. Its restoration, the Falkirk Wheel, the Kelpies and the Charlotte Dundas Trail are a modern reminder of the lasting impact of the waterway and we must continue to cherish it in the difficult years ahead.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.